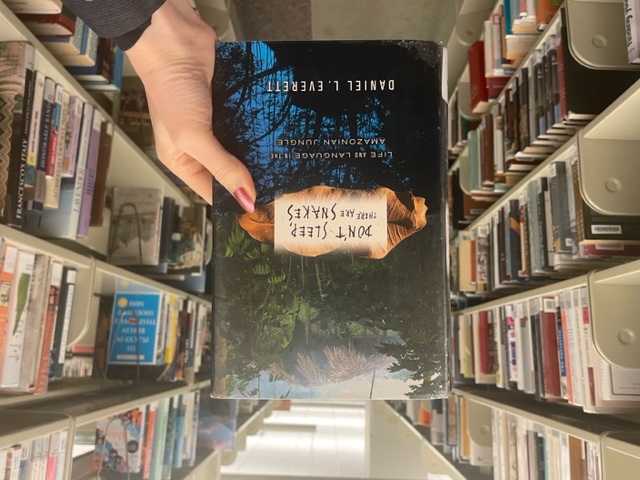

Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes

Reflecting on 2022 through the books I read

Year-end reflections are actually one of my favorite things to do, and although my routine is to do this during the month of December, last month flew by like an uncontrollable storm and here we are well into January! That’s ok. The fact that I might be a little late isn’t going to stop me from engaging in this activity that brings me a lot of joy :) Some of the questions I like to contemplate during my reflections are something like this: What were some of the most memorable moments? Who were the people I grew closer to? What were some things I struggled with? What new things did I try? What were some things that brought me the most joy?

One fun way to consider these questions is by looking back on the books that I read, sometimes with an almost-obsessive enthusiasm. Thinking of all the things that I learned from them (as well as, of course, all the ways I was deeply moved by them), it’s not an overstatement to say that my mind sees the world differently than a year ago because of those books. They say “you are what you eat”, but I’m feeling ever more keenly that my mind is also a direct product of what it consumes. Feeling extra grateful for the encounters with the books that I crossed paths with last year.

A missionary enters the Amazonian jungle. Decades later…

Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes is a work of nonfiction by Daniel L. Everett, who studied, over decades, the language and culture of a hunter-gatherer community in the Amazonian jungle called Piraha.

Early in his career, Everett moves his entire family to a Piraha village as a missionary, and begins his excruciating yet profoundly eye-opening journey. As a missionary, his purpose is to translate the bible into the Pirahan language, but he faces mounting challenges at every step of the way. For starters, the Pirahan language is quite distinct from most of the currently documented languages of the world, which makes it extremely difficult to learn, let alone translate the bible. In addition to this, the extremely isolated jungle poses many physical challenges for Everett, including malaria (with no access to medicine or doctors), roaming taranturas, and an attack by an enourmous anaconda while traveling on a small motor boat.

Everett does an excellent job describing the struggles and frustrations of a field linguist, which is deeply fascinating in itself. However, what is truly exceptional about this book is that it gives the reader a glimpse of the shift in perspective that Everett might have experienced during his time with the Pirahas.

As a missionary, Everett’s initial intention was to “educate” the Pirahas of the “truth” and to offer them “salvation”. However, throughout his journey, there comes a point where he realizes the Pirahas do not need salvation; they are not lost. His story is so rich and profound that I cannot possibly summarize it simply here, but I would like to pull a quote from the final chapter to provide a snippet:

From the time we are born we try to simplify the world around us. For it is too complicated for us to navigate; […] In specific intellectual domains we call our attempts at simplification “hypotheses” and “theories”. Scientists invest their careers and energies in certain attempts at simplification. […] But this type of “elegance theorizing” (getting results that are “pretty” rather than particularly useful) began to satisfy me less and less. People who contribute to such programs usually see themselves as working toward a closer relationship to truth. But as the American pragmatist philosopher and psychologist William James reminded us, we shouldn’t take ourselves too seriously. […] The Pirahas are firmly committed to the pragmatic concept of utility. They don’t believe in a heaven above us, or a hell below us, or that any abstract cause is worth dying for. They give us an opportunity to consider what a life without absolutes, like righteousness or holiness and sin, could be like. And the vision is appealing. It is possible to live a life without the crutches of religion and truth? The Pirahas do so live. They share some of our concerns, of course, since many of our concerns derive from our biology, independent of our culture (our cultures attribute meanings to otherwise ineffable, but no less real, concerns). But they live most of their lives outside these concerns because they have independently discovered the usefulness of living one day at a time. The Pirahas simply make the immediate their focus of concentration, and thereby, at a single stroke, they eliminate huge sources of worry, fear, and despair that plague so many of us in Western societies.

Everett then goes on to talk about how the Pirahas have no craving for truth as a transcendental reality. Indeed, the concept has no place in their values. Their truth concerns catching a fish, rowing a canoe, laughing with your children, loving your brother, dying of malaria. He mentions that some anthropologists have used this fact to suggest that their culture is more primitive, but then leaves us with the question: Is it more sophisticated to look at the universe with worry, concern, and a belief that we can understand it all, or to enjoy life as it comes, recognizing the likely futility of looking for truth or god?