ピダハン 〜「言語本能」を超える文化と世界観〜

読んだ本を通して2022年を振り返ってみると

みなさん、あけましておめでとうございます!!今年の12月はバタバタして、1年の振り返りもろくにする時間も持てずに気がついたら1月となってしまいましたが、振り返り大好き人間な私は、ちょっと遅れてでもと思って今月は2022年に思いを馳せています。どんな心に残る瞬間があったかな〜とか、誰と一緒に時間をたくさん過ごせたかな〜とか、苦戦したのはどんなことだったかな〜とか、新しくチャレンジしたことは何だろうな〜とか、幸福感溢れる気持ちになったのはどんなときだったかな〜とか、そんなことを考えるのが大好きなのです。

これを考える上で結構面白い視点が、読んだ本を思い返すこと。良い本を読んでいたときは、全く違う世界に入り込んだり、今まで全く知らなかったことを学んだり、深く感動したり、今まで背景に溶け込んでいたものが新しい意味を帯びて浮かび上がってきたり、、、もしこの1年で全然違う本を読んでいたら、今の心の感じ方もまた違っていただろうなと真剣に思えるくらい、強く響いた本もたくさんあったと感じます。こうやって改めて振り返ると、出会えた本への感謝の気持ちでいっぱいになります。

ジャングルで狩猟採集民族と共に生活した宣教師に開けた世界

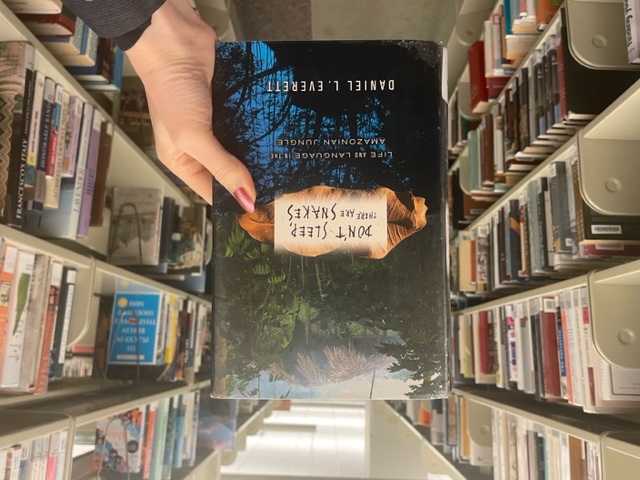

Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes is a work of nonfiction by Daniel L. Everett, who studied, over decades, the language and culture of a hunter-gatherer community in the Amazonian jungle called Piraha.

Early in his career, Everett moves his entire family to a Piraha village as a missionary, and begins his excruciating yet profoundly eye-opening journey. As a missionary, his purpose is to translate the bible into the Pirahan language, but he faces mounting challenges at every step of the way. For starters, the Pirahan language is quite distinct from most of the currently documented languages of the world, which makes it extremely difficult to learn, let alone translate the bible. In addition to this, the extremely isolated jungle poses many physical challenges for Everett, including malaria (with no access to medicine or doctors), roaming taranturas, and an attack by an enourmous anaconda while traveling on a small motor boat.

Everett does an excellent job describing the struggles and frustrations of a field linguist, which is deeply fascinating in itself. However, what is truly exceptional about this book is that it gives the reader a glimpse of the shift in perspective that Everett might have experienced during his time with the Pirahas.

As a missionary, Everett’s initial intention was to “educate” the Pirahas of the “truth” and to offer them “salvation”. However, throughout his journey, there comes a point where he realizes the Pirahas do not need salvation; they are not lost. His story is so rich and profound that I cannot possibly summarize it simply here, but I would like to pull a quote from the final chapter to provide a snippet:

From the time we are born we try to simplify the world around us. For it is too complicated for us to navigate; […] In specific intellectual domains we call our attempts at simplification “hypotheses” and “theories”. Scientists invest their careers and energies in certain attempts at simplification. […] But this type of “elegance theorizing” (getting results that are “pretty” rather than particularly useful) began to satisfy me less and less. People who contribute to such programs usually see themselves as working toward a closer relationship to truth. But as the American pragmatist philosopher and psychologist William James reminded us, we shouldn’t take ourselves too seriously. […] The Pirahas are firmly committed to the pragmatic concept of utility. They don’t believe in a heaven above us, or a hell below us, or that any abstract cause is worth dying for. They give us an opportunity to consider what a life without absolutes, like righteousness or holiness and sin, could be like. And the vision is appealing. It is possible to live a life without the crutches of religion and truth? The Pirahas do so live. They share some of our concerns, of course, since many of our concerns derive from our biology, independent of our culture (our cultures attribute meanings to otherwise ineffable, but no less real, concerns). But they live most of their lives outside these concerns because they have independently discovered the usefulness of living one day at a time. The Pirahas simply make the immediate their focus of concentration, and thereby, at a single stroke, they eliminate huge sources of worry, fear, and despair that plague so many of us in Western societies.

Everett then goes on to talk about how the Pirahas have no craving for truth as a transcendental reality. Indeed, the concept has no place in their values. Their truth concerns catching a fish, rowing a canoe, laughing with your children, loving your brother, dying of malaria. He mentions that some anthropologists have used this fact to suggest that their culture is more primitive, but then leaves us with the question: Is it more sophisticated to look at the universe with worry, concern, and a belief that we can understand it all, or to enjoy life as it comes, recognizing the likely futility of looking for truth or god?